I’ve done a lot of meditating over the years on today’s gospel. For many long seasons of my life, I have felt that I have been with Mary weeping outside the tomb, Jesus calling my name, but I keep failing to recognize Him. Learning to trust Him when I think He’s gone and I can’t recognize Him. (See “While it was still dark”)

Two paintings here of Mary before and after her conversion:

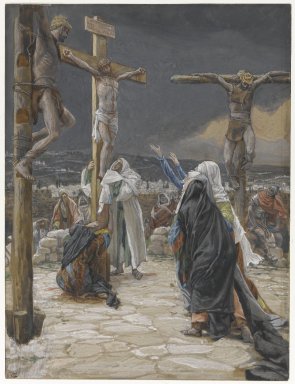

On another note, this poem by Jessica Powers came to mind today. In this poem, she writes about Mary’s encounter with Christ on the Cross and then her later life, where she lived as a contemplative hermit:

The Blood’s Mystic

Grace guards that moment when the spirit halts

to watch the Magdalen

in the mad turbulence that was her love.

Light hallows those who think about her when

she broke through crowds to the Master’s feet

or ran on Easter morning,

her hair wind-tumbled and cloak awry.

What to her need were the restrictions of

earth’s vain formalities?

She sought, as love so often seeks and finds,

a Radiance that died or seemed to die.

One can surmise she went to Calvary

distraught and weeping, and with loud lament

clung to the cross and beat upon its wood

till Christ’s torn veins spread a soft covering

over her hair and face and colored gown.

She took her First Communion in His Blood.

O the tumultuous Magdalen! But those

who come upon her in the hush of love

claim the last graces. A wild parakeet

ceded its being to a mourning dove,

as Bethany had prophesied. We give

to Old Provence that solitude’s location

where her love brooded, too contemplative

to lift the brief distraction of a wing.

There she became a living consecration

to one remembering.

Magdalen, first to drink the fountained Christ

Whose crimson-signing stills our creature stir,

is the Blood’s mystic. Was it not the weight

of the warm Blood that slowed and silenced her?